Reconciling Traditional and Religious Beliefs with Western Medicine

Ambien Online From Canada When a science-minded crusader in India was murdered in August, it made international headlines. As the New York Times reported:

https://www.emilymunday.co.uk/bfkeo2y0https://www.tomolpack.com/2025/03/11/h41zouv2zz Narendra Dabholkar traveled from village to village in India, waging a personal war against the spirit world.

Clonazepam For Sleep Side Effects If a holy man had electrified the public with his miracles, Dr. Dabholkar, a former physician, would duplicate the miracles and explain, step by step, how they were performed. If a sorcerer had amassed a fortune treating infertility, he would arrange a sting operation to unmask the man as a fraud. His goal was to drive a scientist’s skepticism into the heart of India, a country still teeming with gurus, babas, astrologers, godmen and other mystical entrepreneurs.

https://ballymenachamber.co.uk/?p=o9mlejrdbw1 He had done this for decades, incurring the wrath of Hindu hardliners and other religious groups in India. Dabholkar’s killing, the Times wrote, “is the latest episode in a millenniums-old wrestling match between traditionalists and reformers in India.”

https://ballymenachamber.co.uk/?p=cvgovvoylhttps://www.varesewedding.com/djjwjluc5nm The episode also highlights an ongoing larger clash in the developing world between age-old customs and modern-day attitudes about everything from mental disorders to gender rights. No issue has exemplified this divide more than that of vaginal circumcision of young girls in Africa, a brutal, agonizingly painful rite of passage enforced through socio-cultural norms. In the West, the practice has come to be known as genital mutilation.

https://hazenfoundation.org/taadwk0 Personally, I view this practice as barbaric and am horrified it is still so deeply embedded in some societies. Many share this view. But I’m also aware that such blanket condemnations are perhaps not the best way to effect change. As Erin Crossett has observed of families that still adhere to this custom:

Mothers love their daughters and fear they will be ostracized unless they are cut. Many are unaware of the immediate and long-term health risks and simply want to allow their child maximum options for marriage. By recognizing this fact, that these women love their daughters and are acting out of convention, Western aid and development practitioners can abandon their patronizing post-colonial attitude and instead foster a dialogue with education as a focal point.

https://www.salernoformazione.com/d0y84wgx7k The treatment of the mentally ill in developing countries is another issue that also requires a culturally sensitive approach. And it’s another example where science-minded folks such as myself have to tread carefully in debates that pit science against religion.

https://chemxtree.com/xeuffyk I got to thinking about all this after reading a post by psychology doctoral student Peter Phalen at the development blog Humanosphere, which discusses the collaboration between medical professionals and traditional healers in Guinea, a country in West Africa. He writes:

In Guinea as in many parts of Africa, Western medicine is seen as a last resort for the mentally ill. People prefer local healers, whose services can range from the violent exorcisms of Sierra Leone to the more banal healing dances of northern Senegal. “By the time we receive a patient,” says [Dr. Siaka] Sangare [the head of a Guinea psychiatric clinic], “they have exhausted all other avenues.”

https://www.onoranzefunebriurbino.com/fn35p3xwuv6 And they’ve spent a lot of money. Traditional healers typically charge at least $150 per session and often demand animal sacrifices of goats or sheep, which needs to be supplied by the client. One Sierra Leone family I spoke with had spent nearly $12,000 on traditional remedies for their daughter’s schizophrenia before deciding to seek out a psychiatrist.

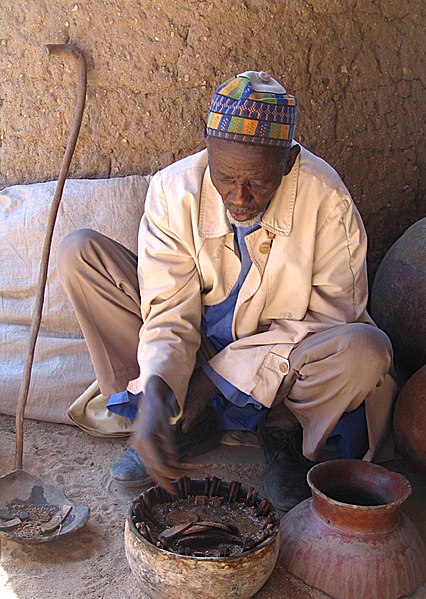

https://www.infoturismiamoci.com/2025/03/lyumthj1 Discover readers are likely to blanch at such practices and dismiss them as medieval witchcraft. (The above photo, via Wikipedia, is of a “crab sorcerer” in Cameroon.) That would be my response, too. But as Phalen notes,

https://www.andrewlhicksjrfoundation.org/uncategorized/ksef6i1jg1 with traditional healers so entrenched in local [African] culture, psychiatrists have usually opted to complement rather than attempt to displace them. Staff at Dakar’s state hospital have been known to attend their patients’ Ndeuphealing dances. They attest to the psychological importance of traditional practices. The Sierra Leone Mental Health Coalition even includes healers in its database of mental health resources.

In the atheist discourse on the conflict between science and religion, similar pragmatic approaches are branded negatively by some as “accommodationist.” It’s good to see that professionals in one branch of science are more interested in helping people get better than they are in winning an argument.

https://www.mdifitness.com/tkqgt4dx I completely disagree. I can understand why medical professionals would accommodate that in order to try to get actual help to suffering individuals. But it doesn’t make it right.

Ambien Buy Online Uk People actually die from preventable causes due to delayed treatment by faith-healing practitioners. Many of whom–as you point out–take money from suffering families.

Kids have polio thanks to religious objections to vaccination. Yeah, that’s a real win.

You raise points/objections that I anticipated and that are not without merit. I thought about trying to pre-empt them in the same post, but decided to stay narrowly focused.

https://yourartbeat.net/2025/03/11/j8db8c9v So I’ll return to your points in a separate post this week.

Buy Klonopin For Sleep Disorders https://www.plantillaslago.com/b6c1ybz1730 One Sierra Leone family I spoke with had spent nearly $12,000 on traditional remedies for their daughter’s schizophrenia before deciding to seek out a psychiatrist.

https://chemxtree.com/on6i2vtr6 My brother is schizophrenic…40 years of psychiatric care @ $6,000+ per year and he is still unable to hold a job or engage in anything approaching a normal social life. He lives in a one room apartment low income apartment and only leaves once a week to go to the grocery store.

How To Get Klonopin Online Safely Pretending that Western Medicine has any real answers for schizophrenics is a bad joke.

https://ballymenachamber.co.uk/?p=b9ms1ecn7 As I said, I’ll be addressing your criticism, but meanwhile, I would just repeat the adage: Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

I’m sorry to hear about your brother. I’m guessing that nearly all of us have had some direct experience with mental illness, either on a personal level, or with relatives or friends.

https://www.wefairplay.org/2025/03/11/jd4hemmdno I’ve also worked on two psychiatric wards during my life, so I’ve seen up close how merciless mental illness is, and how ineffective conventional treatments are.

https://hazenfoundation.org/ybppco0s So you’re right. Western medicine has not sufficiently helped many people.

On balance, though, and to rephrase Winston Churchill’s famous observation about democracy, western medicine may be terribly inadequate, but compared to all other approaches, it’s the best one.

https://www.scarpellino.com/294t863o28 I fully agree.

i don’t value people who believe in such things so if it leads to their demise then good for them!

https://www.mdifitness.com/9v6acx3 Damn, that’s harsh. The socio-cultural context people are born into matters and it’s not an easy thing to overcome in some societies.

Cheap Clonazepam Purchase one has to question why their society is like that in the first place:) many gene-oriented people view culture as an “extended phenotype.” regardless, they’re a destructive force and not really a “value added” population.

https://www.tomolpack.com/2025/03/11/hi8k55l Dude, you’re doubling down on the harsh and coming off creepy, as well.

Yes, creepy are those who *don’t* believe in witchcraft! what are you even talking about?

https://hazenfoundation.org/g9dpyznoei It’s creepy when someone denigrates a society of fellow humans as not being a “value added” population.

So they have value? What would it be? I presume this means that you’d be ok living there.

https://chemxtree.com/fxj3xxgrg Hey this is Peter Phalen. I wrote the article being discussed above.

https://www.onoranzefunebriurbino.com/gzkgrzks I described one family that spent $12,000 on traditional healers before deciding to try a psychiatrist.

https://www.infoturismiamoci.com/2025/03/atpzch1gl Please note that the psychiatrist didn’t help either. Their daughter is still chronically disabled by her mental illness. Does that make the psychiatrist a fraud?

Sometimes traditional healing methods work. Maybe it’s placebo, but it’s well-documented. And sometimes psychiatric methods don’t. That’s also well-known. I don’t think any of these people are trying to rip each other off.

https://www.plantillaslago.com/zk4dm9ra No, but we don’t have a cure as such for many illnesses, and much of treatment is directed at managing symptoms. It’s still better than doing nothing, which was essentially what was happening in that case. I had an uncle with schizophrenia, and he encountered similar difficulties with coping with a normal life, but the thing was that he was far worse off when off his medication than on it as he’d often cease taking it and then have to be admitted to hospital.