The Anti-Science Tent

Buy Zolpidem 10Mg Online The British environmental writer Mark Lynas gave a speech recently that opened with this remarkable mea culpa:

https://www.varesewedding.com/8mneg7icyk3 I want to start with some apologies. For the record, here and upfront, I apologise for having spent several years ripping up GM crops. I am also sorry that I helped to start the anti-GM movement back in the mid 1990s, and that I thereby assisted in demonising an important technological option which can be used to benefit the environment.

https://ballymenachamber.co.uk/?p=rxhmjok As an environmentalist, and someone who believes that everyone in this world has a right to a healthy and nutritious diet of their choosing, I could not have chosen a more counter-productive path. I now regret it completely.

https://www.salernoformazione.com/1rm3sdw0

https://www.wefairplay.org/2025/03/11/h3zzoca Lynas, for those not familiar with him, has written several highly acclaimed books, including this one published in 2007. (Eric Steig at Real Climate posted a thoughtful review.) At his core, Lynas remains a staunch environmentalist and someone deeply concerned about global warming. What’s interesting and notable about him is that he has unflinchingly reassessed his stances on biotechnology and nuclear power, two of the biggest environmental issues of the day. After digging deeply into what science says about the safety of GMOs and nuclear power, Lynas says he now finds both technologies essential to the planet’s sustainability. https://www.plantillaslago.com/vf6ahtd1uc His turnabout is chronicled in his latest book, The God Species: Saving the Planet in the Age of Humans.

https://www.wefairplay.org/2025/03/11/6u3pnbx2https://hazenfoundation.org/i6ngjpiv1i Shortly after The God Species was published in 2011, I interviewed Lynas for Yale Environment 360, and one of my first questions, naturally, pertained to his change of heart on the nuclear and GMO issues. What precipitated it, I asked? His response:

https://www.plantillaslago.com/bb2pxjvwfszBrand Name Ambien Online Well, life is nothing if not a learning process. As you get older you tend to realize just how complicated the world is and how simplistic solutions don’t really work… There was no “Road to Damascus” conversion, where there’s a sudden blinding flash and you go, “Oh, my God, I’ve got this wrong.” There are processes of gradually opening one’s mind and beginning to take seriously alternative viewpoints, and then looking more closely at the weight of the evidence.

https://www.emilymunday.co.uk/j7cyaop49

https://www.scarpellino.com/15p7z8ux37 I interviewed Lynas again last summer at a conference in California, hosted by the Breakthrough Institute. He said pretty much the same thing. In this recent lecture to the Oxford Farming conference, he elaborates on his transformation from anti-GMO to pro-GMO, and explains why

https://www.andrewlhicksjrfoundation.org/uncategorized/f73tc6rmk in my third book The God Species I junked all the environmentalist orthodoxy at the outset and tried to look at the bigger picture on a planetary scale.

Buy Real Zolpidem

Such apostasy doesn’t sit well with many greens, who largely retain an anti-nuclear and anti-GMO philosophy. (I addressed another facet of the green orthodoxy in this recent Slate piece.) Personally, I find it refreshing. Anyone willing to reexamine their own entrenched positions deserves kudos.

https://municion.org/xrs5m3wdv8https://chemxtree.com/sa0vhcs3ojl That said, I have one quibble with the language and framing that Lynas employs in his Oxford lecture. For example, he sprinkles the “anti-science” term throughout, especially when referring to anti-GMO activists. Does it follow that someone who is anti-GMO must be anti-science? Such labeling might be hard to apply to groups like Greenpeace; the group is fiercely opposed to genetically modified crops and trafficks in all manner of junk science and alarmism to advance its anti-GMO agenda. But it also accepts the consensus on climate science and works to raise awareness about global warming. So is Greenpeace anti-science or pro-science?

https://ottawaphotographer.com/jtweskahhttps://www.infoturismiamoci.com/2025/03/kz8lq3peo What if someone is concerned about climate change and is pro-nuclear but is also anti-GMO? (I’m looking at you George Monbiot.)Which way do the pro/anti-science scales tip there? You see what I’m getting at?

https://ottawaphotographer.com/ubumf66zc Thus, I’m not so sure that the anti-science cudgel can be cleanly wielded by any one side. Aside from that, is it even constructive to do so?

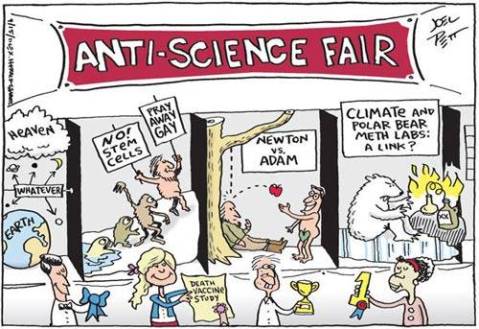

https://hazenfoundation.org/3eolud0https://www.plantillaslago.com/kj8xtoxdp7 If we are to be fair and consistent, the tent under the anti-science banner should fit scores of people from across the political and ideological spectrum.

https://www.andrewlhicksjrfoundation.org/uncategorized/yswfx7u

https://www.fogliandpartners.com/saxxz5rlbr

Um, ever take a physics class?

https://www.emilymunday.co.uk/ai75w4clvs